The History of Gauze is Haunting Me

Fabric is culture, culture is passport, and home should not be bloody.

I’ve been staring at versions of this grid for weeks as my tiny happy place from the chaos of being inundated with holiday sales and horrific news cycles. Going online has felt so wild lately - you can’t really avoid swinging back and forth from images of violence and reports on the genocide of Palestinians and the state-sanctioned celebration of it, the sterilized newsroom framing of it, to like, shopping promotions and viral memes. To have any kind of ‘business as usual’ mode feels kind of disgusting, no? I am unable to metabolize the level of grief and outrage I feel into much more than nausea and fog and hyperfocus on things that are materially kind of unimportant.

I have been preoccupied with the history of fabrics. Maybe because interesting textile work is the unifying factor of my current moodboard, but also because textile work is culture work, is cultural history, is a diary entry, a passport, a wrapping, someone’s dreams made manifest and another person’s daily wages. “Whoever says Industrial Revolution,” wrote Eric Hobsbawm in Industry and Empire, “says cotton.” Textiles and industry, fabric and culture - they’re woven together, forgive the wordplay. Think of the fabrics of today, the degradation of quality you find in most stores at the moment - you can get clothing in fast fashion stores, yes, but it quickly decays, and the laborers behind the clothes are often no better off for the deal either.

Right now, I’m really drawn to knitwear, reclaimed textiles as new designs, to one-of-one pieces - because of the immediate connection to the person who made it, but also because the quality is better. The motivation behind the finished garments isn’t a trend or a purchase order to finish but a question to the universe that something thoughtfully made would find a person who might see it, love it, ask about it like it’s an old friend. How long did it take to get here, to my arms? Did you dye the wool yourself? The beads in the embroidery - how long did they sit in your studio, waiting for their moment? What draws you to collecting certain buttons, since each are different? I spent hours in a boutique recently chatting with one of the designers behind Colorant about how they decided on the colors of their sweaters, how long the dye process takes, the back-and-forth process of fabric collection for reworked jacket pieces. It felt like we were best friends in her living room, so quick was the camaraderie over clothing.

Fabric is an intimate thing to me, not only because it is literally clothing my body but because it’s a pathway to learning about other people. To learn about fabric means you inevitably learn how things are made, what was involved, and who was committed to the act of creating something. Knitwear, embroidery…they require dedication, human dedication, to happen. From the newest fabric to the oldest ones around.

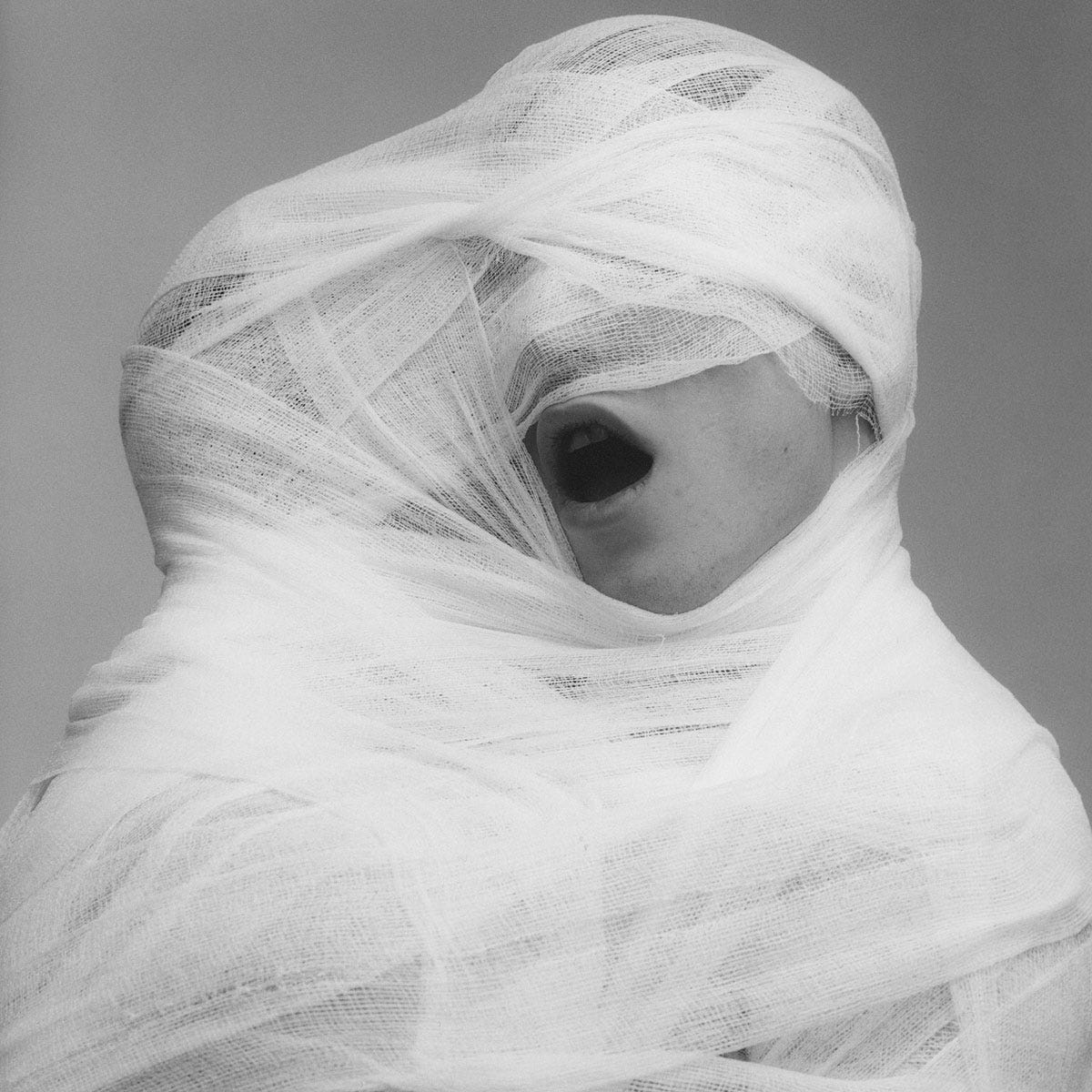

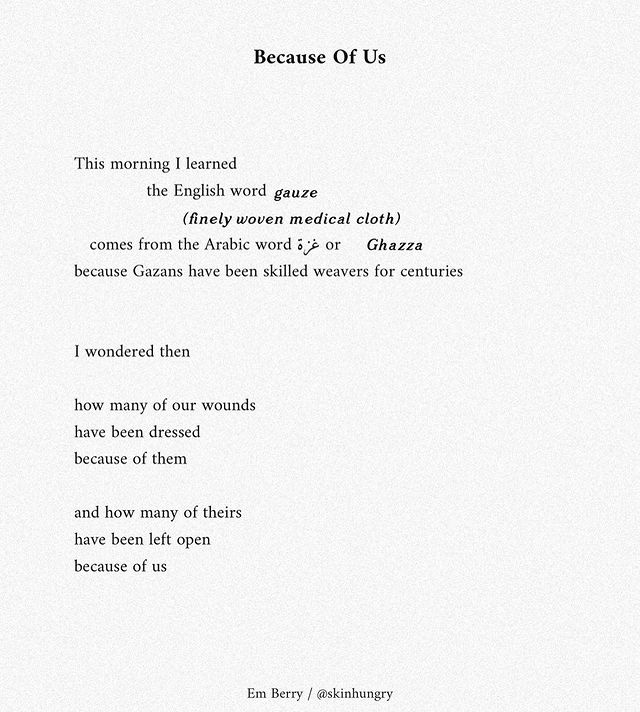

A few weeks ago, I came across the knowledge that gauze - the word and the cloth itself - comes from Gaza. Gauze, that lightweight open-weave cotton fabric, breathable, forgiving, found in any well-stocked First Aid Kit and certainly any medical establishment - it’s from Gaza. It was originally made of silk and used in clothing, and now it is made of silk, cotton, and other kinds of fabrics. But the origins lie in Gaza, a place now being utterly decimated, where the hospitals are bombed, where surgeons are having to perform on children, often their own, with no anesthesia, no medications, no sterilized environment and often no…gauze. To have given the world something synonymous with care, with healing, and to be deprived of it so utterly - is that not the saddest, most haunting thing?

Knowing this has haunted me every day. I don’t know what to do with this information besides collect it, honor it by linking it to all the other things I know and cherish. Share it with you, so you might mourn with me.

I’m keeping busy, being haunted by this knowledge and the grief the context summons. The injustice of it does move me to do things. You know - read-ins for Palestine, passing information along, caring for friends and organizing in the ways that I can, where I am, with what I know. It’s been hard to be a person and I am not a productive person this year, but I think not being able to be productive is a normal, healthy human response to utter destruction and witnessing the dehumanization of people in real time. The fact I can still find beauty and pleasure in material things is a lifeline for my sanity, a little moat of hope for better things in a sea of absolute garbage. You can witness horror and be broken by it, but the breaking of you - of us, me - is a win for those who would break much more and do so gladly. I am choosing every day to refuse to be broken entirely. I consider beautiful things memorials to the people who made them, who perhaps saw enough goodness in the world to embroider them into physical memory or weave it into being. Who might not have seen it but wanted to, so badly, that they made it.

Learning about fabrics post-haunting has led me to many projects of grief-weaving. one in particular I can’t stop thinking about is the NAMES Memorial Quilt Project.

Conceived by gay rights activist Cleve Jones, who had helped in the campaign to elect Harvey Milk in San Francisco and who had witnessed his later assassination, it is 48,000 quilted memorial panels to people lost to the AIDS crisis. Jones came up with the idea of a cloth memorial when his friend Marvin Feldman died, and he made the first commemorative panel in his honor. The NAMES Project was established in 1987 and its aim was to invite people to make a sewn panel, each bearing the name of someone who died of AIDS. As the writer Claire Hunter describes it, “he wanted to create a fabric requiem that lamented the waste of so many lives through negligence and fear, on a scale and impact that would make its message escapable and could campaign for more resources to stem the epidemic.” By October 1987, the first nearly 2,000 panels were laid out in the Mall of Washington D.C. It became a fabric garden, one you had to crouch down to examine, kneel and prostrate on to read all the names. Most of the panels were sewn by novices, the loved ones left behind, the panels made of their clothes - sports jerseys, ties, t-shirts, sometimes hospital bedding. Every panel, a universe of love and grief, named and honored in a collective as far as the eye could see. A roll call of the names woven took 24 hours in 1992. It has kept growing. There are now 48,000 panels.

When I think of how we might honor and remember those who have died - and are dying - right now, this moment, in Gaza, I’m wondering what that might look like. The numbers keep growing, the numbers are debated, the numbers are not enough to understand the loss, really. Every number is a universe, every person is important to somebody. I pray every day my life is never reduced to a number, a line in a spreadsheet. I do stay up a night thinking of my life reduced to a panel, though. What would your panel look like, if you died? How do you honor a life, really? Another thing that haunts me. All I know is that if there were a quilt, any weaving, of what is happening, it must include gauze. And still, no matter how beautiful, no matter how intricate the embroidery - it would make up for nothing. I don’t think humanity deserves gauze, but I’m grateful for it, for what is has given us, for the unfair and still forgiving fact of its beauty.

Today is the last day of the End of the Year Newsletter Sale. There are only ever two a year. Your support means the world to me, whether you are a paid subscriber or on the free list. Thank you for reading.

This is really lovely, thank you.